Chapter I. Childhood

Festival in Urbino and little Rafael. - Father. -Name Santi. - Urbino. - “Chronicle”. - Mother. - Father's influence. – Madonna Giovanni Santi. – Talent of a youth .

In the middle part of eastern Italy, not far from the shores of the Adriatic Sea, on a rocky mountain rises a small but ancient city Urbino, surrounded by ancient fortress walls.

Exactly four hundred years ago, a particularly solemn day turned out to be a particularly solemn day for residents of the city, as well as surrounding villages. The young Duke of Urbino Guidobaldo, a seventeen-year-old youth who had already managed to cover himself with military glory in the ranks of the papal army, this time returned to his hometown as a peaceful winner; Elizabeth Gonzago, the beautiful and highly educated daughter of the Duke of Mantua, was the trophy of this victory and henceforth became the ornament and glory of the ducal court. In the 15th century, Italians easily found excuses for festivals, public ceremonies, masquerades and processions. The city of Urbino could not equal Florence and Rome in their fabulous splendor, but the inhabitants of the city, subjects of the Duke, were second to none in their diligent service and devotion to their master. It was not only the youth and generosity of the Duke, together with the beauty of the Duchess, that aroused general joy. It was also facilitated by the memory of Father Guidobaldo, the famous Duke Federigo da Montefeltro, distinguished by his love of science and art, courtesy and patronage of scientists and artists, which covered his name with even greater glory than military honor and knightly valor.

The whole city, like the castle, was decorated with colorful carpets and garlands of flowers. Across the street leading to the castle stood triumphal arches, decorated with paintings by the best artists of that time. There was no shortage of music, singing, allegorical and clownish processions, or luxurious costumes.

The young Duke paid citizens with hospitality in his luxurious castle. Within the walls of the latter was a vast courtyard, surrounded, like an ancient circus, by an amphitheater, erected, according to the plans of the late Duke, in order to observe public games. Here city youths took part in a game called “Aita”. It consisted in the fact that all the youth were divided into two parties, attacking one another, and each tried, by overpowering his opponent, to drag him to his side. Whichever side later had more of these “prisoners” was considered the winner. Those who were distinguished by their particular dexterity and courage received rich gifts from the generous duke, the approval of the crowd and their chosen ones.

A charming child caught the attention of the audience present. He was a six-year-old boy with regular facial features, unusually clear eyes and light curls. The child looked with big eyes at the rapid movements of the beautiful, dexterous young men, at the splendor and luxury that surrounded him. Rushing forward, he held the woman's hand; it was his mother, wife famous artist Giovanni Santi, who played a significant role in organizing the festival and in decorating the courtyard with paintings.

The boy's name was Raffaello. Nature endowed him from birth with meekness and beauty of body and spirit. The whole world knows him now under the name Rafael Santi, or simply Raphael.

Raphael's father, Giovanni Santi, a famous artist in his time, whose merits, as well as his influence on Raphael, are still debated, wrote a poem that is usually called a chronicle, since it, despite its rhymed form, contains there is very little poetry and no artistic significance. Moreover, perhaps, it wins in the sense of a chronicle of contemporary events for the author, a description of the court of Duke Federigo, his personality and the artists, poets and scientists around him. In the dedication of this poem or chronicle, as we will call it, to Duke Guidobaldo Giovanni complains about his fate: “Fate sent severe trials my father's house. The flame destroyed our home and all our property, so it takes a lot of time to tell all the disasters that accompanied my life.”

In fact, Raphael's great-grandfather, named Peruzzolo, a modest inhabitant of the small town of Colbordolo, became a victim of one of the wild outbreaks of internecine hostility that tormented unfortunate Italy so much in the Middle Ages. In 1446, Count Sigismundo Malatesta, with papal soldiers, devastated the land of Federigo, then Count of Urbino, with fire and sword, and Peruzzolo, among others, lost his home and had to abandon the devastated land. He moved with his family to the city of Urbino, where he hoped to find reliable shelter and food. For a long time However, the family had to struggle to escape extreme poverty. There is still a house where the whole family lived, paying 13 ducats a year for rent. This house belongs, just as at that time, to the spiritual brotherhood of St. Mary the Merciful. Peruzzolo died when Giovanni, his grandson and future father Raphael - was still young. Father Giovanni bore the name Santa, given to him at baptism. In Italy it was not customary to have a surname, and only later they began to call Giovanni after his father Santa or Santi, and from Latin translation- Sanctius - this name turned into the name Sanzio, which began, although incorrectly, to be attached to the name of Raphael.

So, Giovanni Santi had reason to complain about fate. But, having traced later life father and Raphael himself, we will be amazed by the expedient course of events, by the chain of happy accidents that fate forged for its brilliant chosen one.

Santa, Raphael's grandfather, soon made a fortune for himself through a happy, albeit petty trade in antiquities. He first purchased a plot of land for 240 ducats from Paltroni, the count's secretary, then he also bought land and a well-irrigated meadow, and finally, again for 240 ducats, he bought two houses located one next to the other on the Contrada del Monte street, leading from the trading area to the castle . Together they formed one of the most significant houses on this street. Here, in this very house, Raphael saw the light, according to Vasari, in Good Friday, March 28, 1483.

Until the age of 11, Raphael grew up in his father's house, until the latter's death in 1494. Not only this period of childhood, but also the following years of Raphael’s youth remain unclear to his biographers. There is even evidence that during his lifetime his father himself apprenticed him to Perugino. It is more accurate, however, that until the age of eleven, Rafael did not leave his father, but was already studying and even helping him in his work. Early development Raphael, undoubtedly, if we take into account how quickly he showed Perugino not only mastery in painting, but a certain originality and independence of his talent, which was not yet strengthened at that time. That is why one should recognize the undoubted influence of his father and childhood impressions on him, even in the relatively early period of the latter.

Although the city of Urbino was not the birthplace of Giovanni Santi, he breathed his clean mountain air since childhood. Like frozen waves of the sea, mountain ranges rise from the shores of the Adriatic, and where they reach greatest height, on a rocky slope lies this city, surrounded by strong walls. A vast horizon opens up to the eyes of the city dweller, reigning over the entire surrounding area. Nature and art came together to influence the spirit of the inhabitants, strengthening their courage and elevating their aspirations.

The ruler of the area in the second half of the 15th century, Count Federigo from the Montefeltro family, with the pride of a noble knight and a glorious warrior, combined the courtesy and modesty of a highly educated man. In his free time from military activities, he was tirelessly engaged in the construction and decoration of the castle and the city. The famous architect Luciano da Laurana built a new palace for the Duke, and connected the old one with two ancient towers that stood on separate rocks. This enterprise, which cost enormous sums and energy, lasted for many years under the constant supervision of the Duke, who invariably encouraged the working artists with generosity, kindness and friendly conversation.

The Duke gathered around him many famous names at that time to decorate the palace with paintings and sculpture. Art brought beauty and harmony into the atmosphere of the courtyard, which spread far around from here.

Under the influence of this atmosphere, Giovanni Santi abandoned the studies he had inherited from his father and turned to painting. He himself says in his chronicle that this decision increased his household worries, especially since the latter are especially difficult for one who has risen above them in soul and taken on his shoulders a burden heavier than the burden of Atlas - service to art; he was not ashamed, however, even in poverty and hardship, to bear the name of an artist.

We can already see from here that Giovanni’s thoughts and feelings fully corresponded to the mood and views of that bright period of time - the dawn of the Renaissance. He passed on this elevated mood, this belief in the purity and holiness of art to his son. At the same time, he passed on to him part of his knowledge and experience, allowing him to help him in his work and talking with enthusiasm about famous artists, their lives and work, about the love and worship with which the people surrounded them, about the patronage of noble rulers and beautiful ladies. And he not only told all this to his son, but also left it after his death as a testament, capturing his stories in a detailed description - in his famous chronicle, which, among other things, is not devoid of poetic beauty, as can be seen from the fact that some, although exaggeratedly, they called him “the second Dante” (!).

It is unknown who Giovanni Santi’s teacher was, but it follows from the same chronicle that he studied everywhere and from everyone, wherever he could get something. With surprise and gratitude, he recalls the famous artists of his youth and especially praises the virtues and knowledge in art of Andrea Mantegna, to whom, in his words, “heaven itself opened the gates of painting.”

“Particularly dear to my heart,” he notes in another place, “is Melozzo da Forlì, who made enormous strides in the study of perspective.” The last remark probably gave reason to look for the origins of Santi’s education in the influence of the named artist. Whether this is solid or not, one thing is clear from the remark, namely, that Giovanni was already aware of the imperfection of his native Umbrian school - the lack of knowledge and understanding of nature.

From here there remains only one step in the direction of the Florentine school, and we will see how quickly Raphael goes along this path. No wonder Giovanni is amazed at the genius of Leonardo da Vinci and in his artistic wanderings studies the works of Tuscany, Venice and Lombardy, admiring the beautiful Madonna of Fra Angelico da Fiesole and the paintings of the famous Piero della Francesca.

The latter visited Urbino in 1469 and lived in Giovanni's house. At this time, he painted portraits of Duke Federigo and his wife Battista Sforza, which are now kept in the gallery of Florence.

Santi also could not escape the influence of Verrocchio, a student of Donatello, one of the first and most powerful prophets of the Renaissance, one of the founders of the Florentine school.

Few of Giovanni's paintings survive locally in Italy, and the fewest remain in Urbino. Some were damaged or disappeared during revolutionary struggle, others were appropriated by the foreign conquerors of Italy, which indicates the value attached to them.

In the last years of his father's life, Raphael already accompanied him to the nearest cities and monasteries, where Giovanni had orders. This gave Raphael a happy opportunity not only to see many significant things in such early age, but also to learn the imaginative legends of that time, either at the place of stay or during the journey. These stories, like the Italian imagination of that era in general, were permeated with images of a wonderful sky, natural abundance, the energy of freedom and spiritual spontaneity.

Religious feeling, reaching the point of mysticism and superstition, gave the paintings, especially the images of the Holy Virgin, a special charm of meekness, peace, spiritual clarity and purity. These paintings belonged to the brush the best masters, and were the decoration of monasteries and churches where Giovanni worked. Still almost a child, Raphael in his native city was already near his father during his work in the churches of Urbino and here he studied and breathed the atmosphere of an unearthly life, often filled with a special peaceful joy and quiet fun.

In his hometown, Giovanni Santi had his own workshops on Via del Monte, where he carried out regular orders for paintings and gilding frames for Urbino churches. The latter specialty was then combined among the masters with painting, because for a long time it was the custom to decorate a picture with a gilded background. However, it is known that in the Middle Ages artists were usually very versatile people. We will see later what various works: artistic, architectural and decorative - lay on Raphael at the papal court. The famous Cellini, who created “Perseus,” was called a “goldsmith,” and in fact he was famous for his jewelry art: the diamonds in his setting did not lose, but also gained in brilliance. The brilliant sculptor was proud of this art.

His father's workshops and inheritance, that is, a house and land, enabled Giovanni to live comfortably. He was married to the daughter of an Urbino merchant; Her name was Maggia, she was the mother of Raphael.

From his father, Raphael inherited a passion for art, adoration of beauty, striving for perfection and sensitivity; from his mother - the spiritual clarity and meekness of the peaceful mood that breathes through all his paintings. She approached in character and appearance the type of Madonna that Giovanni painted, and the latter therefore perpetuated her image. On one of the walls in the courtyard of the Santi house, a fresco was found depicting the Holy Virgin with a baby in her arms. She sits on a bench, her gaze fixed on the book spread out in front of her and tenderly holding the sleeping baby to her chest. There is so much life in this group that the painting was long attributed to the son instead of the father. The naturalness in the position of the figures and the especially successful gentle profile and subtle expression of sadness - everything suggests that the picture was painted with special love and that Giovanni’s model was his young wife and her first son.

After some time, Maggia left the world, leaving Raphael an eight-year-old orphan. True, Santi soon married again, but this second wife did not become a second mother for the boy and generally did not have the same beautiful, feminine character as Maggia.

No reliable news has been preserved about the first attempts of Raphael’s brush during his father’s lifetime. Much is attributed to him by oral and written tradition in precisely those paintings of Santi that were destroyed, often together with the altars and walls of churches that contained them.

As for the teachings of Raphael, legend says, among other things, that he studied the Latin language in Urbino under the guidance of the famous Francesco Venturini, the first compiler of a complete Latin grammar and teacher of the great Michelangelo. If this is so, then even then Raphael must have heard something about this famous titan of art (albeit still a young man), and the teacher’s stories, of course, aroused the zeal of the impressionable boy.

Everything heard and seen in childhood leaves an indelible mark. The stronger this influence resonates in the soul of a brilliant child. The Duke's court and castle, games and festivities, the luxury of the colors of the sky and greenery, extensive views of the surrounding area high up standing city, the powerful spirit of its ruler, the cheerfulness and clear mood of the guests and artists who visited the Santi house - these are big picture the situation that influenced Raphael. The chronicle left by Giovanni reveals his education, knowledge, observation, emotional impulses and love of art. But the mother, in addition to her character, contributed her share to the child’s education. At this time, when the individuality of the Renaissance man was being formed, the woman was not a slave, she brought her personal taste, views and influence into the home. She herself received an education in her parents' house, often the same as a man, and sometimes even more extensive. The sum of all these influences constitutes the wealth acquired by Raphael in adolescence.

Rafael Santi. Madonna in green. 1505 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

To judge what Raphael took from Urbino in a purely artistic sense, let's look at what his father did.

Despite the fact that Santi began painting quite late, the number of his works is very significant, and among them the image of the Madonna is especially often repeated. The individual nature of the beauty of the Madonna who decorated the wall of his house was not accidental, but more or less distinguishes all her images by Giovanni. In one of his paintings in the church of Santa Croce (in Fano), the children's heads with their charm, as Passavan says, already foreshadow the angels of Raphael, and the coloring of the bodies of the angels differs so little in some paintings of father and son that it is often difficult to decide reliably whose brush they belong.

It is also noticed that Raphael’s faces of little angels are for the most part very reminiscent of the same faces painted by his father. The latter, however, often painted the image of his beautiful son on the canvas, so that in Raphael’s paintings we sometimes see his own face at different periods of childhood. He was, in fact, so handsome that as a child he partly resembled Botticelli's angels.

One of the features of Giovanni’s creative style is also the depiction of the landscape in the painting. True, this was only the “embryo” of the landscape, and Raphael went much further in this sense. We will see why at this time the landscape began to play a significant role and how Raphael’s genius took advantage of this; but it should be noted here that picturesque nature The homeland of Raphael and his father most of all contributed to the emergence of this particular feature in them.

If Giovanni did not occupy last place among his contemporaries, he also did not get ahead of them. He did not deviate far from the accepted forms of composition, but he already had a presentiment of the coming reforms and enthusiastically walked towards them. That is why he so admired the successes of exemplary artists in knowledge of perspective and in the study of nature. The aspirations of his soul went further than the form he owned. It was not he, however, who was destined to give his son the necessary tools for success. This fell to the lot of those who laid the foundation of future art, making it necessary for the artist to study anatomy, ancient beauty and colors.

There is still no movement in Giovanni's paintings. His figures froze in silent peace. The raised hand remains as if petrified. There are no paintings by Santi in our Hermitage, but the same can be seen in many paintings by his contemporaries and predecessors. His works often reveal, however, the personalities of individuals, and the manner of depiction already more or less reveals the originality of the master, the desire to be faithful to nature, to living reality. With a certain rigor, he captures either the serious character or the attractive charm of a child’s face. He had not yet achieved perfection, but he strived for it, always remaining receptive; These qualities - desire and receptivity - he passed on, as already noted, to his son.

The divine genius of Raphael tore the latter from the earth and carried his imagination to another, higher region, to those spheres where the gaze of a mere mortal cannot look; he saw beauty itself, wheezing on the throne - she gave him a brush and paints, “opened his eyes,” as Jehovah once did to his prophets. Therefore, Raphael cannot be called a student of his father, just as he cannot be called a student of Perugino, or even Michelangelo. From his very first steps, he amazed his teachers with the uniqueness of his genius; they were amazed at him, almost becoming his students. But genius will not escape the influence of time and space, as well as the influence of people, and a significant share in this overall influence belongs to Raphael’s father, Giovanni Santi.

From the book Boris Pasternak author Bykov Dmitry LvovichChapter II Childhood

From the book Call Sign – “Cobra” (Notes of a Scout special purpose) author Abdulaev ErkebekChapter 4. Childhood I was born on January 31, 1952 in the village of Beisheke, Kirov district, Talas region, Kirghiz SSR. Our family consisted of 14 mouths, including two grandmothers and three nephews with two working parents. My father was a director at that time. high school. Mom is in the same

From the book by Prishvin authorChapter I CHILDHOOD Writers are not made - they are born. Prishvin himself, however, stipulated: “Almost everyone is born a poet, but very few become poets. The poet lacks the effort to jump on his wild horse.” In the mid-twenties he would write one of his best books

From the book Prishvin, or The Genius of Life: A Biographical Narrative [Journal version] author Varlamov Alexey NikolaevichChapter 1 CHILDHOOD Writers are not made - they are born. Prishvin himself, however, made a reservation: “Almost everyone is born a poet, but very few become poets. The poet lacks the effort to jump on his wild horse.” In the mid-twenties he would write one of his best books -

From the book The Adventures of Conan Doyle by Miller RussellChapter 2 Childhood ARTHUR IGNATIUS CONAN DOYLE was born in Edinburgh, at number and Picardy Place on May 22, 1859. Two days later he was baptized catholic cathedral St. Mary's, right next door. His godmother was his great-aunt Catherine Doyle, a nun from

From the book My Icebreaker, or the Science of Survival author Tokarsky LeonidChapter 2 Childhood I was born on July 2, 1945. And he was the fourth son of my parents. As far as I know, there were brothers older than me by 12 years, 8 years (Borya) and 4 years. I don’t know what happened to my two older brothers. I assume that they died during the blockade. Mom absolutely

From the book Bekhterev author Nikiforov Anatoly SergeevichChapter 1 CHILDHOOD The winter that year was snowy, the frosts were severe: the birds froze in flight. And the hut is heated, stuffy... Early morning. The light barely glimmers through the curtained, blind-sighted windows... The newborn screamed and calmed down. His mother, Maria Mikhailovna, is in

From the book Kuprin is my father author Kuprina Ksenia AlexandrovnaChapter VI CHILDHOOD Memories early childhood sometimes they are very bright, and not so much environment, people, how many feelings - love, hatred - take on enormous proportions in children and remain in memory for the rest of their lives. And, oddly enough, now that a difficult and

From the book Ludwig van Beethoven. His life and musical activity author Davydov IAChapter I. Childhood Family. - “The old bandmaster.” - Father. – First music lessons. - Pfeiffer. - Eden. - Nefe. - Introduction to life Ludwig van Beethoven - Dutch by birth - was born in Bonn (on the Rhine) and was baptized on December 17, 1770; his birthday

From the book by Freddie Mercury. Stolen Life author Akhundova MariamCHAPTER I. CHILDHOOD The first thought that arises when getting acquainted with materials about Freddie Mercury: it is amazing that such a great man has such poor biographies. There is not even a hint of professional work with information in them. Or rather, they contain no information at all, how

From the book My name is Vit Mano... by Mano Vit From the book by Andrei Tarkovsky. Life on the Cross author Boyadzhieva Lyudmila GrigorievnaChapter 1 Childhood The brighter the childhood memories, the more powerful the creative potential. A. Tarkovsky 1Andrei Tarkovsky was lucky with heredity. He was lucky, if we take as a result the seven and a half films that he managed to contribute to the treasury of world cinema, and do not remember

From the book Lodygin author Zhukova Lyudmila NikolaevnaChapter 3. Childhood The roads in Stenshino are still country roads today. In winter - on the crisp crust, and in summer, when it's dry, it's a pleasure to ride along them: all around, for many miles, the steppe is as smooth as a table, only tiny islands Here and there you can see groves and whitewashed village huts. And in the spring,

From the book The Book of Life. Memories. 1855-1918 author Gnedich Petr Petrovich From the book by David Garrick. His life and stage activities author Polner Tikhon IvanovichChapter I. Childhood One spring evening in 1727, Mr. Garrick's house was strongly illuminated. The small town was already asleep, and it was even stranger to see the movement and bustle in the modest home of the poor lieutenant commander. In a “big” room, usually closed and dark,

From the book of Bach. Mozart. Beethoven author Bazunov Sergey AlexandrovichChapter I. Childhood Family. - “Old bandmaster.” - Father. – First music lessons. - Pfeiffer. - Eden. - Nefe. - Introduction to life Ludwig van Beethoven - Dutch by birth - was born in the city of Bonn (on the Rhine) and was baptized on December 17, 1770; his birthday

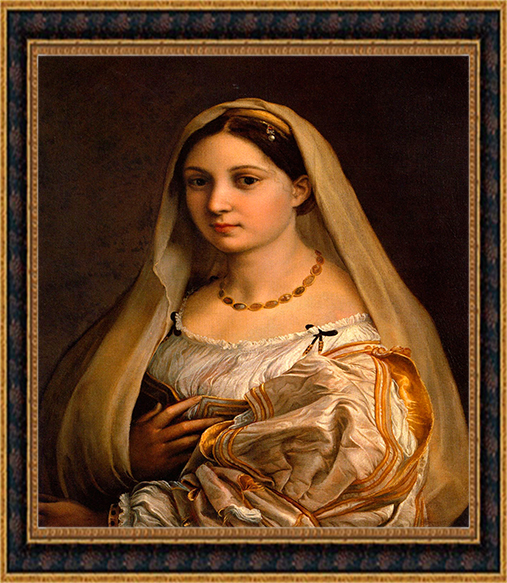

The most famous painting by the great Raphael Santi (1483–1520) depicts the image of a young and very beautiful woman with huge black almond-shaped eyes. The prototype of the “Sistine Madonna” was Margarita Luti, the most powerful and desperate love of a beautiful genius.

Raphael Santi was born on April 6, 1483 in the family of the court poet and painter of the Dukes of Urbino, Giovanni Santi. The boy received his first drawing lessons from his father, but Giovanni died early. Raphael was eleven years old at the time. His mother died even earlier, and the boy was left in the care of his uncles - Bartolomeo and Simon Ciarla. For another five years, Raphael studied under the supervision of the new court painter of the Dukes of Urbino, Timoteo Viti, who passed on to him all the traditions of the Umbrian school of painting. Then in 1500 the young man moved to Perugia and began studying with one of the most famous artists of the High Renaissance, Perugino. The early period of Raphael’s work is called “Peruginian”. At the age of twenty, the painting genius painted the famous “Madonna Conestabile.” And between 1503 and 1504, by order of the Albizzini family, the artist created the altar image “The Betrothal of Mary” for the Church of San Francesco in the small town of Città di Castello, which completed the early period of his work. The great Raphael appeared to the world, whose masterpieces the whole world has been worshiping for a century now.

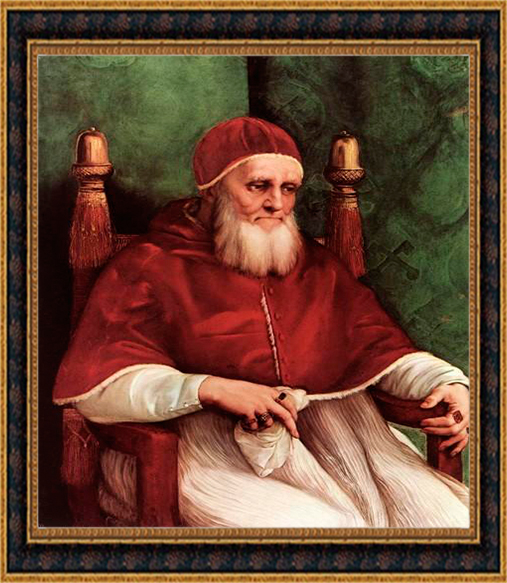

In 1504, the young man moved to Florence, where Perugino’s entire workshop had moved a year earlier. Here he created a number of delightful paintings with “Madonnas”. Impressed by these masterpieces, in 1508 Pope Julius II (reigned 1503-1513) invited the artist to Rome to paint the state apartments in the old Vatican Palace.

So it began new stage in the life and work of Raphael - the stage of glory and universal admiration. This was the time of patron popes, when the world of the Vatican Curia was dominated, on the one hand, by the greatest debauchery and mockery of everything honest and well-behaved, and on the other, by admiration for art. The Vatican to this day has not been able to completely cleanse itself of the stains of atrocities committed by pope-patrons under the cover of the papal tiara, and philosophers and art historians have been unable to explain why, precisely in an era of blatant depravity, in the very epicenter of depravity art, architecture and literature rose to unattainable heights.

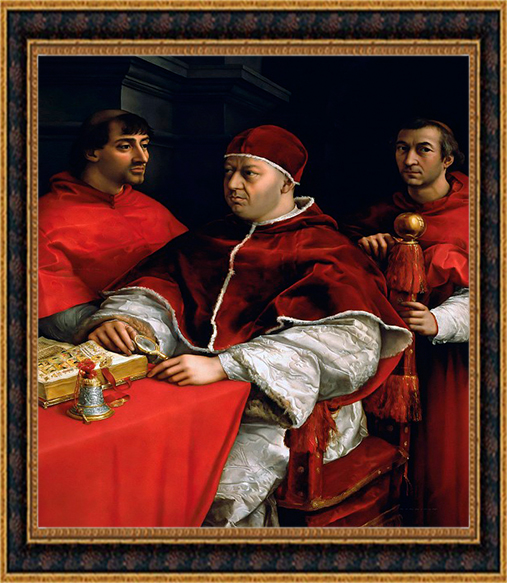

After the death of the depraved old man Julius II, the papal throne was taken by the even more depraved Leo X (ruled 1513-1521). At the same time, he had an excellent understanding of art and was one of the most famous patrons of poets, artists and actors in history. The pope especially favored Raphael, who he inherited from his predecessor, who painted buildings and palaces and painted delightful paintings.

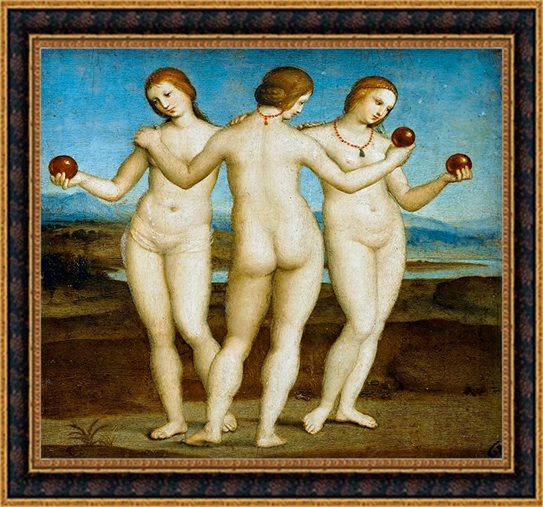

At the same time, a noble and rich man lived in the Eternal City - Agostino Chigi, the owner of many estates and lands, the owner of the huge Farnesino Palace in Rome. Following the traditions of the papal court, where it was customary to imitate the tastes of the pontiff in every possible way, Chigi invited Raphael to paint the walls of the central gallery of the Farnesino Palace. Soon the artist created here the magnificent frescoes “The Three Graces” and “Galatea”, but for the third fresco “Cupid and Psyche” Raphael could not find a model.

One day the artist was walking through the park and admiring picturesque landscapes palace park. In the shade of the trees, he suddenly noticed a girl resting. Her angelic face was so carefree and pure that Raphael was confused. They say that the artist instantly forgot all the girls whose attention he had never been deprived of. The girl stole the show. Fascinated by her unearthly beauty, Raphael exclaimed: “I have found my Psyche!” The painter asked the girl: who is she and where is she from? She, embarrassed, replied that she lived nearby, and her father was a baker. The girl was seventeen years old, and her name was Margarita Luti.

Raphael invited Margarita to his studio and asked her to pose for his portrait. She, a little embarrassed, replied that she had to ask permission from her father and her fiancé, the village shepherd, whom she was soon to marry.

When parting, Raphael gave Margarita a gold necklace and asked her to accept it as a token of gratitude for a wonderful day. The girl refused the gift. Then the artist offered her a small deal - ten kisses for an expensive necklace. The deal was completed.

Inspired and happy, Raphael could hardly wait until the next morning and hurried to the baker. The girl's father, having received several gold coins from the artist, allowed his daughter to pose for the painting.

Raphael painted Margarita in his studio. Stately and handsome man with refined features and dark, curly hair I couldn’t help but please the ardent girl. The artist was over thirty, but he was still very handsome. Roman beauties admired him, noble women became his mistresses, but only “little Fornarina,” as the artist nicknamed the girl, made his heart tremble.

Soon Raphael was no longer satisfied with the posing sessions. He became jealous of Margarita, did not sleep at night, drawing in his imagination pictures of the girl’s meetings with her fiancé, the shepherd Tomaso. Finally, the artist could not stand it. He paid Margarita's father 3,000 gold pieces and took his beloved to Rome. The girl became Raphael's mistress, the mistress of his heart. The artist fulfilled all her wishes: he bought her expensive clothes and jewelry, surrounded her with luxury and wealth, assigned her numerous servants who fulfilled every desire of the young beauty. But the insidious and calculating Fornarina was mainly interested in the money of an unexpected patron. She constantly exhausted the artist, remained unsatisfied and demanded more every day. To the young creature there was little affection and admiration. She demanded not only new riches, but also wanted Raphael not to leave her side for a moment and indulge in the pleasures of love only in her company. And the artist obediently fulfilled these whims, literally burning in the arms of his insatiable mistress.

The hour came, and Agostino Chigi urgently asked the artist to complete the commissioned work at Farnesino. Understanding the situation, Chigi promised to provide the loving couple with special apartments in the palace, where Margarita could hide from her friends.

The lovers were forced to return. Having learned that his bride was hiding in the palace, the shepherd Tomaso sent her a threatening letter. He cursed Margarita, showered her with furious reproaches and threatened to take revenge. Fearing that his threats were not empty words, the cunning woman called Chigi and told him about the threats of her ex-fiancé. Agostino, in turn, invited Margarita to become his mistress. And unexpectedly she promised the confused Agostino everything he wanted, but on one condition: if the mighty lord imprisoned his shepherd Tomaso in a monastery. That same evening the poor shepherd was captured, and the beautiful "Psyche" betrayed herself. love pleasures in the company of Chigi, distraught with happiness.

Soon it became known about another love story beautiful Fornarina. She dragged into her bed a very young young man from Bologna, Carlo Tirabocchi, who took lessons from the great master. Raphael's students considered this betrayal offensive to themselves and challenged the young man to a duel. The ill-fated Carlo was struck by a blow from a sword and soon died from loss of blood. But nothing could stop Margarita; soon she had a young lover again.

Raphael tried to turn a blind eye to his beloved’s numerous romances, remained silent when she came only in the morning, as if he did not know that “his little Fornarina,” his beautiful Baker, became one of the most famous courtesans of Rome. And only the silent creations of his brush knew what torment tormented the heart of their creator. Raphael suffered so much from the current situation that sometimes he could not even get out of bed in the morning. He went to the doctors and was diagnosed with severe exhaustion of the body. The artist was given bloodletting, but it only made the master feel worse. The exhausted heart of the genius stopped on April 6, 1520, on his birthday.

Raphael was buried in the Pantheon, where the remains of the greatest people of Italy rest. The artist’s students blamed the unfaithful Margarita for the death of their teacher and vowed to take revenge for the fact that through a series of countless betrayals she broke the heart of a great man.

Frightened Margarita ran to her father, in whose house she hid for some time. Here she once came face to face with her ex-fiancé Tomaso, who, by her grace, spent five years in monastery captivity. Margarita found nothing better than to try to seduce him, and bared her lush shoulders in front of the shepherd. He grabbed a handful of earth and threw it in his face. ex-fiancée and left, never to see the woman who ruined his life again.

The inheritance Rafael left would have been enough for the frivolous Fornarina to change her life and become a decent woman. But, having felt the taste of carnal love and carefree life, having known the most famous men Rima, she did not want to change anything. Until the end of her days, Margarita Luti remained a courtesan. She died in the monastery, but the cause of her death is unknown.

Raphael's picturesque creations adorn the most famous museums peace. Moreover, thanks to them, in particular, these museums became famous. Millions of people every year freeze in admiration before the image of the “Sistine Madonna,” which has long become the main treasure of the Dresden Gallery. They look with tenderness at a beautiful, unearthly woman holding out a trusting baby from heaven to them... But few people know that the earthly flesh of the woman depicted in the picture once belonged to the most voluptuous and dissolute courtesan of Italy - the one who destroyed a genius in the prime of his strength and talent.

However, another version of the events described is also found in the literature. From the very beginning, Raphael fell in love with a depraved Roman maiden, he knew her worth very well, but in the immoral atmosphere of the court of patron popes he did not hesitate to use her as a model when painting faces Mother of God. Margarita Luti had nothing to do with the early death of the artist.

“Beautiful as Raphael’s Madonna” - these words have been the highest praise for the spiritual and physical beauty of a woman, a hymn to clear and bitter maternal happiness for more than four centuries. Researchers of the work of the genius of the Renaissance were surprised by the fact that all the images of Madonnas of the Roman period of the artist’s work are united common features. Who was the woman he painted with such ecstasy? For a long time, the legend of Raphael's beautiful lover Fornarina was considered a myth.

Love and deceit. Genius and villainy. How often the sublime and the base go together. Our world is imperfect, but Raphael’s work has become synonymous in art with a sense of proportion, beauty and grace. Among the huge number of paintings, images of Madonnas became a sacred and inexhaustible theme for the artist. According to G. Vasari, they seem “rather sculpted from flesh and blood than from paints and designs.”

Many romantic legends are associated with the name of Raphael; his life is shrouded in speculation. Outwardly sociable and open, the artist was rarely frank with anyone; he had many acquaintances, but few friends. Friends included students and heirs, his estate D. Romane, F. Penney, as well as famous people of that time: A. Chigi, B. Castaglione, B. Bibbiena, P. Bembo. From the letters of the last two, individual information about Raphael’s personal life, his hobbies and entertainments is mainly gleaned. Most likely, it was from their memories that the name of the artist’s mistress, Margarita Luga, appeared, and then for some reason two biographies of her appeared at once. One was based on the sublime bright love girls to Raphael. From the other, she appears as the greatest villain who charmed the genius and brought him to the grave.

Raphael was that happy chosen one for whom creativity was not a painful search for an unattainable goal. His innate sense of proportion, exceptional sense of space, balance and harmony gave birth to the art of “eternal beauty” - calm, sublime, ideal. The artist did not strive for in-depth comprehension inner world a man like Leonardo da Vinci, the colors in his paintings did not burn with fire, like Titian’s, he was not disturbed by the spirit of tragic rebellion of Michelangelo. He “happily did not notice the discord between ideal and reality.” Raphael's classical art is synthetic, musical and surprisingly proportionate.

The brilliant development of his talent as a painter is associated with the spiritual and artistic environment in which he was born and raised. Raffaello was born in the small mountain town of Urbino (Umbria) on April 6, 1483 in the family of the painter and humanist poet Giovanni Santi (Sanzio). His father married late, taking as his wife the daughter of the Urbino merchant Maje Chiarle. Of their three children, only the eldest, Raffaello, survived. The highly educated Giovanni taught his son his first painting lessons in his workshop and managed to instill in the boy love and admiration for art. At the court of the Urbino Duke of Montefeltro, where Santi worked, a sophisticated, intellectual atmosphere reigned. And the legacy of such great masters as Piero della Francesca and Donato Bromante, who worked in Urbino, became the ideal environment in which his son’s artistic talent flourished.

Rafaello was left an orphan at an early age. He was only eight years old when his mother died, and three years later he lost his father. Uncle Simone Ciarla took care of the boy. They did not forget about him at court either. He continued his studies in his father's workshop, which was led by assistants, and then, in 1500–1505, with Pietro Perugino, the head of the Umbrian school of painting, trustingly following his manner. The student adopted from his mentor the softness and smoothness of lines and an ideal sense of composition.

The young artist had many orders in Siena. But captivated by the stories of eyewitnesses about the “battle of the giants” - the picturesque competition between Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, “forgetting about his benefits and conveniences,” he moves to Florence. Always ready to gain new knowledge and experience, Raphael independently began studying the diverse achievements of Florentine art, without interrupting creative activity. The artist gained enormous fame for his numerous (at least 15) Florentine Madonnas, attracting with their diversity and classical perfection of artistic solution to one theme. The images of the Mother of God by Raphael, having lost their former fragility and contemplation, were filled with an earthly maternal feeling, which is so close and understandable to every person. Their outer beauty is inseparable from spiritual perfection and nobility (“Madonna of the Green” and “Madonna with the Beardless Joseph,” both 1505; “Madonna of the Goldfinch,” c. 1506; “The Beautiful Gardener,” 1507) .

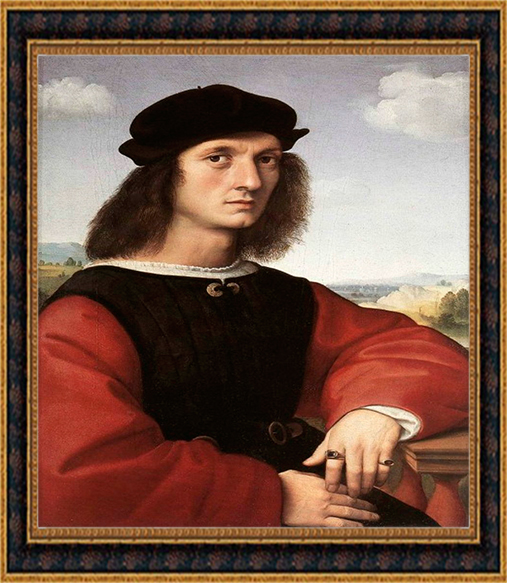

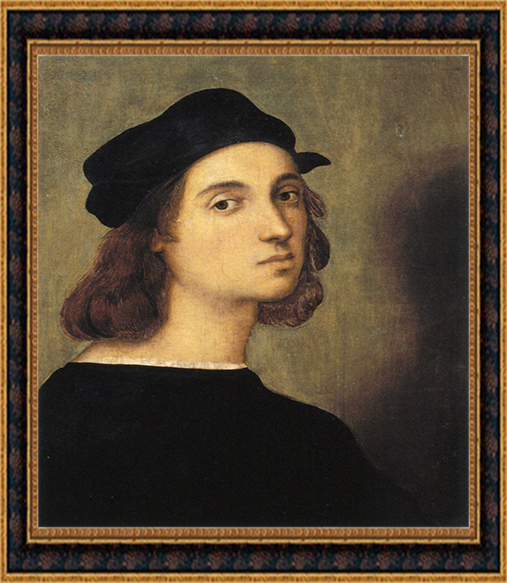

“Beautiful as Raphael’s Madonna” - these words sound like the highest praise for the spiritual and physical beauty of a woman, a hymn to the clear happiness of motherhood. This topic was inexhaustible for the artist, and it is unlikely that even a hundred years of life would have been enough for him to realize the hundreds of sketches and sketches that gradually filled numerous folders. The Florentines quickly appreciated the “master of Madonnas.” The fame of an artist and an educated gallant man flew ahead of him. Raphael attracted people with his rare spiritual qualities, with which, according to Vasari, “so much grace, hard work, beauty, modesty and good morality were combined” that he could be considered not a man, “but a mortal God.” The self-portrait, painted in 1506, represents a man whose communication extinguished all “displeasures” and “all sorts of base and evil intentions. Throughout his life he never ceased to show best example how we should treat both our equals and those above and below us.” He never competed with anyone, did not envy anyone, and did not criticize others. Instead, Raphael enjoyed life, the world, people and the opportunity to create. The artist never looked for friends and patrons. He was surrounded by them, like a prince by his retinue. And therefore, it is not surprising that thanks to many recommendations, including from the Duke of Urbino della Rovere (nephew of Pope Julius I) and the papal architect Bramante, who worked on the decoration of the Vatican, Raphael, in the 25th year of his life, was invited to the papal court.

Arriving in The eternal City, he discovered that most of The palace halls have already been fully or partially decorated by other painters. But Julius II, captivated by Raphael’s “genius of good nature” and the artist’s first sketches, instructed him to re-paint the three Vatican stanzas (rooms) intended for the pope, removing the more eminent masters - Perugino, Sodoma, Bramantino, Peruzzi. The painter of meek, thoughtful Madonnas with amazing speed became an incomparable master of huge fresco paintings.

In the ideally balanced scenes of “Disputations”, “The School of Athens” and “Parnassus”, inscribed in the complex architectonics of the chambers, one cannot add or subtract the slightest touch so as not to disturb the “strictly verified harmony of the perfect whole”. A clear sense of composition and impeccable mastery of space allowed Raphael to picturesquely talk about the beauty of a rational, perfect person - the ideal of the Italian humanists.

The work in the stanzas captivated Raphael, but it was so enormous that the artist gradually acquired numerous assistants and students, “whom he helped and guided with purely paternal love. Therefore, when going to court, he was always surrounded by fifty artists... In essence, he lived not as an artist, but as a prince,” wrote Vasari. Raphael entrusted the painting of the third “Stanza del Incendio” (1515–1517) based on his paintings to his favorite student Giulio Romano and other young artists. Not a single master could boast of such mutual understanding and friendship that reigned in Raphael's school.

But no matter how busy the artist was in the Vatican, he created many works for his friend and patron, one of the richest and influential people Rome, banker and merchant Agostino Chigi. Raphael did not stop working on altar images (“Madonna della Tende”, ca. 1508; “Madonna Alba”, 1509; “Madonna with a Fish”, “Madonna del Impannata”, both in 1514). But if the Florentine Madonnas are touching young mothers, absorbed in caring for the child, then the Roman Mothers of God are bright goddesses, bringing to the world spiritual harmony of sacrifice, regardless of whether they reign over other figures (“Madonna di Foligni,” 1511–1512) or are resolved in an intimate genre (“Madonna in an Armchair,” 1514–1515).

The highest achievement of Raphael's artistic genius was the Sistine Madonna (1513–1514). The artist entrusted all the Vatican works to his students in order to paint with his own hands a large altarpiece for the monastery church of St. Sixtus in distant little Piacenza - his most famous painting. He worked joyfully and quickly and created a unique image of the Mother of God, combining in it the divine beauty of a woman-mother and the highest religious ideal. “The curtain parted, and the secret of heaven was revealed to the eyes of man... In the Mother of God walking through heaven, no movement is noticeable; but the more you look at it, the more it seems that it is getting closer,” the poet V. Zhukovsky wrote about the painting. Everything about her is incredibly simple, but the longer you look into Mary’s anxious eyes, the more you realize the tragic sacrifice to which the mother of the future God voluntarily doomed herself. Her unseeing gaze is extraordinary big eyes clouded by worry about his son. For centuries, Raphael's "Madonna" has become the artistic personification of motherhood, spiritual beauty, bitter happiness and martyrdom. And there is no more perfect Madonna in the world than the Sistine.

Typicality of some female images Roman period is associated with the fact that the model for them was Raphael’s beloved, nicknamed Fornarina. This woman with noble features, whom he loved until his death, is also depicted in the portrait “Donna Velata” (or “The Veiled Lady”, 1514), which is one of the greatest masterpieces of the High Renaissance. It is she who is sometimes called Muse, sometimes evil genius Raphael. Their love story years later I received two “scenarios”, although the outline of life in both versions is the same.

The successful Siena baker Luti was expelled from one city by the tyrant Petrucci. He fled to Rome with his daughter and sister and here he turned for help to his fellow countryman, Agostini Chigi, whose wealth and power extended all the way to the papal throne. So he acquired a generous patron who gave him a small house and provided him with a loan. The baker hired apprentices and assistants. These nimble young men did not take their eyes off his beautiful daughter Margarita, nicknamed Fornarina - the Baker. She was only 17–18 years old, but according to the customs of that time, she was already a girl of marriageable age and had a fiancé, Tomaso Cinelli, a shepherd on one of the cabbage soup estates. The walls of his country villa Farnesina were painted by Raphael at that time. One day he noticed a girl walking in the park and realized that her beauty was worthy of being captured forever. Margarita pretended to be modest and sent the artist to her father and fiance to ask for permission.

They say that for 50 gold coins, the baker allowed Raphael to draw his daughter as much as he wanted, and took over negotiations with his future son-in-law. Tomaso, looking forward to the wedding, began to reproach Margarita for her intention to change her word: after all, Raphael, like most rich men of that time, led a dissolute life, using the services of courtesans different levels. To get rid of her obsessive groom, who had become an obstacle to unprecedented wealth, the girl solemnly vowed in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo to marry him. Tomaso had no doubts left, because she clearly belonged to him in body, and now, as he believed, in spirit.

Margarita herself did not even suspect who she had caught in her net. Spoiled by the love and admiration of women, Raphael fell in love for the first time. He showered this angel with gifts, received her as an eminent guest and drew, drew, drew. At first, Fornarina modestly remained a model. The only night Raphael spent with an “absolutely innocent” but experienced woman made the artist lose his head. For three thousand gold coins, the father, who does not suffer from prejudices, allowed him to take his daughter for any period of time.

Raphael settled Margarita in a luxurious villa, dressed her like a princess, showered her with jewelry and even abandoned work. For a whole year he neglected the orders of Pope Julius II, believing that the stanzas in the Vatican were less important than a beautiful insatiable mistress. And Agostino Chigi, irritated by the suspension of work, invited Raphael to settle in his Villa Farnesina - of course, together with Margarita. The clever intriguer made no mistake here either. Justifying that because of her, her beloved was losing orders, and therefore money and fame, she agreed to leave “their nest.” Fornarina herself pursued two goals at once: to protect herself from the groom angry at the betrayal and to get closer to a richer and more powerful patron - Chigi.

The aging banker fell for the “youthful charms” of Margarita, which she shamelessly offered him. He saved her from Tomaso's "harassment". The shepherd was tied up and taken to the monastery of Santo Cosimo, whose abbot, cousin Kiji undertook to keep him in prison as long as necessary.

Two influential lovers were not enough for Margarita; she shamelessly flirted with Raphael’s students and assistants, although they avoided any contact with her. The artist remained unaware of the treachery of his beloved. He did not listen to the admonitions of his friends and students. They say that in one of the conversations between the talented students of the artist Perino del Vaga and Giulio Romano, the latter frankly admitted: “If I found her in my bed, I would rather turn the mattress over to the other side than lie down next to her.” In 1518, the young Bolognese Carlo Tirabocchi set his sights on Fornarina. He was even proud that he was sleeping with his teacher’s mistress, and he considered the fact that the other students broke off all relations with him to be envy. The young people quarreled. The matter ended in a duel. Perino del Vaga killed Tirabocchi. The truth was hidden from Raphael. And Fornarina soon found a replacement for the Bolognese.

Only for Raphael, no woman could replace Margarita. For six years, he worked during the day and turned his nights into an exhausting love fire, on which his health burned. The artist was weakening before our eyes. The doctors, not knowing the reasons for the ailment, bled him over and over again. But as soon as Raphael got better, he again fell into the vampire arms of Fornarina. The artist's physical strength has dried up. The cardinal, who brought the last blessing from Pope Leo X, demanded that the corrupt woman be expelled from the dying man’s room. Margarita clung to the legs of the bed and perfectly feigned despair. Only in the last hours of his life did Raphael realize: the woman he portrayed as the bright Madonna had a black soul.

Margarita did not grieve for the deceased. According to the will, she received a decent amount and could continue to conduct luxurious life. Special patronage she used Agostino Chigi. Other wealthy men did not let the chic courtesan through. She even offered her arms to her ex-fiancé, who had fled the monastery, but Tomaso contemptuously threw a handful of earth in her face. Margarita Lugi ended her life in the monastery, but how she got there and when she died is unknown. This is the first version of the love affair between the beautiful Baker and the great Raphael.

But is it possible that an artist, reading human souls by the eyes, could not notice the base thoughts reigning in this charming head? After all, it was not for the sake of a “red speech”, not for the sake of the desire to cleanse the image of Raphael from filth, that a second legend appeared - pure, sublime, ideal, like the works of the artist himself.

Raphael was brought to the home of baker Francesco Luga by the patron of the family, Agostino Chigi. One glance was enough for the artist to understand that he had never seen such a beautiful woman as Margarita. She looked like a beautiful sculpture: a chiseled figure, a soft neck line, breasts filled with youthful juice, lips that were small by classical standards, and a nose a little longer than necessary. But the eyes... Dark, glowing coals. There is so much life, kindness, and affection in them. Margarita also looked closely at the famous artist: she looks like a young prince, although he was over 31 years old, his manners are refined, but without arrogance, and he addresses her, the daughter of a simple baker, as a noble patrician. And when he smiled, the girl felt that she had met the most beautiful man. It was not without reason that they said that Raphael created harmony around himself and attracted people to him with rare spiritual qualities.

Raphael asked Margarita's father for permission to draw her, and promised to give one of the sketches to the girl. Agostino Chigi immediately calculated in his mind how many weighty ducats such a sketch could cost, because cardinals and dukes competed with each other for the honor of having a painting by Raphael. The first sessions took place under the vigilant supervision of the aunt. The artist caught himself thinking that he dreamed of being alone with the girl, and sometimes he came to his senses and remembered that he had promised to marry the niece of the influential Cardinal Bibbien, Maria Dovizi, and immediately drove these thoughts away from himself. Rafael delayed the sessions as best he could, and when his aunt left them for a minute, they simply looked at each other. Under his gaze, Margarita blossomed like a wondrous flower.

“I submitted, became a victim of the heat of love,” Fornarina once read in one of the sketches. She immediately believed that these lines were dedicated to her, and agreed to a date at dusk at the Church of Santa Maria in Truste Vere, located in the quarter of the poor, where morals were simpler, where an honest girl could go in the evening unaccompanied. They talked and kissed. Raphael confessed his love, but immediately warned, without disclosing the reasons, that he would not be able to marry: he had a debt to his bride, and biographers believe that Pope Julius II promised the artist the rank of cardinal (which, naturally, excluded marriage). This could well be allowed, because at the age of 25 he received the “place of secretary of the apostolic breves” - a very significant rank even for young prelates.

Rafael gave the girl the right to make her own choice. Fornarina agreed: between shame and the monastery, she chose love. The artist confided in his plans to Agostino Chigi and bought a house from him for 4,000 ducats in a new area of Rome, where no one knew Margherita. To avoid unnecessary talk about her as a kept woman, he notarized half of the house in her name. The lovers chose the time to move when Francesco Lugi left the city on business as a banker. Only a few rooms in the house were put in order, and there was not enough furniture. All the artist’s funds were spent on buying a home, but he did not skimp on dresses, shoes and jewelry for his beloved. Margarita's beauty received a worthy frame.

The girl was afraid to even leave the house. Among her new acquaintances were only the artist’s students and assistants, as well as the “beautiful Empire” - a former famous courtesan, and now the faithful lover of Agostino Chigi, who bore him a daughter. Two beautiful women they found a common language: they had nothing to share, each loved her man, each knew that she would never become the legal wife of her lover. The Empire had long come to terms with this, but Margarita was just beginning to get used to it. On the advice of an educated courtesan, knowledgeable in art and literature, she began studying Greek language, read a lot to be worthy of my brilliant beloved. But all her self-doubt disappeared as soon as Rafael returned home after a long day of work. Fornarina never asked him questions that troubled his soul, did not make demands, and did not even suspect what a wave of interest and rumors she had caused with her appearance in Raphael’s house. Their life remained a mystery to all of Rome. And they loved each other selflessly, and just as selflessly he painted her portraits: dressed in a rich patrician dress, naked, covered only with a light, transparent veil, and, of course, the Madonna. It seemed to Margarita that it was at these hours that they were especially close. She could patiently stand at the window all day for bright moments of happiness.

Margarita saw with what love Raphael applied every stroke. Maybe that’s why the lines in the portraits flow, forever capturing the rarest standard of unclouded female beauty. Fornarina felt these gentle touches of the brush with every cell of her body. And Rafael before last days life was captivated by its perfection, warmth and tenderness. “I am defeated, chained to the great flame, which torments and weakens me. Oh, how I burn! Neither the sea nor the rivers can extinguish this fire, and yet I cannot do without it, since in my passion I am so happy that, while flaming, I want to blaze even more.”

Because of this passion, from year to year he put off the need to marry the cardinal's niece, making excuses big amount orders. And this was also true. Last years Raphael worked his butt off throughout his life. In addition to the position of court painter at the papal court in 1514, the duties of the chief architect of the Vatican were added, and a year later - the “commissioner of antiquities”, “prefect of all stones”. This work, especially the protection of monuments of Roman antiquity, took a lot of effort and time. And he also really wanted to transfer into the paintings new incarnations of Margarita, whose face radiated a sea of kindness.

It was then that the artist created a unique image of the “Sistine Madonna,” tremblingly transferring onto canvas the features of his only beloved, Margarita Luga. Raphael could paint such a bright image of a woman only by looking into clear eyes in which a crystal clear soul shone.

Six years of quiet home happiness and hard work. Margarita saw how fatigue fell on her beloved day after day: dark shadows under the eyes, lack of appetite, sleepless nights. He never got tired of her presence and was never bored next to her. Since the death of the Empire, Margarita had no friends left, and with the move to new house, which was located in an aristocratic area, she even stopped going for walks. Any day Fornarina could return to her father’s roof, because her father called her and promised that her daughter would not hear a single reproach. Francesco Lugi had long since paid off his debts and was now prospering. With an appropriate dowry, Margarita could become the wife of some apprentice or artisan. Raphael wrote down two thousand ducats in the bank in her name, “untying her hands,” and the banker looked at his friend’s woman with an inviting look. But Margarita knew that if Rafael ever left her, she would no longer need anything. Even after moving with the artist to Villa Agostino, where Raphael painted the walls, she did not succumb to the temptation to replace the owner of the Empire. Fornarina posed to create images of the mythological beauties Psyche and Venus. The frescoes at Villa Farnesina became another monument to the artist’s love for Margarita.

Raphael was staggering from fatigue. After another trip to the quarries, where they found an antique statue, he came down with a fever. Physical strength, unlike creative ones, turned out to be not limitless. The artist managed to bequeath his fortune to his only beloved woman, friends and students. Margarita received half a house, six thousand gold ducats and the unfinished painting “Madonna with a Bird” in her will.

“In conclusion, I consider the virgin Maria Bibbiena, whom, due to many affairs and troubles, I was not able to lead to the altar as my wife. She can call herself, if it pleases her, the wife of our pure union.” Have you heard these words of Fornarina's will? After all, she did not leave Rafael’s bed for a minute, changed compresses, fed him fruit. When Cardinal Bibbiena came to give absolution and asked the woman to leave the house, she was worried about only one thing: who would supply the medicine, change the linen, and cook the soup. She seemed rooted to the ground. No one heard what Margarita quietly said to Raphael before leaving; only the artist’s muffled voice reached the cardinal: “I love you very much...” He understood why his niece remained a bride. “I will take you to the carriage, Madonna Margherita,” said the prelate, seeing how, without making a single sound, so as not to disturb her beloved, she sobbed in the next room.

Margarita awaited her verdict at Villa Chigi. Raphael died, mourned by all of Rome, on his birthday, in Good Friday, April 6, 1520. He turned 37 years old. He was buried in the Pantheon. Maria Dovizi, the niece of Cardinal Babbiena, was buried next to the artist’s tomb as his bride...

One of his contemporaries, reporting the death of Raphael, wrote: “His first life ended; his second life, in his posthumous glory, will continue forever in his works." The great artist died out along with his era: with the death of Raphael " High Renaissance the painting had its say the last word" And few people noticed that life in the world had ended for Fornarina. She did not take advantage of the enormous wealth. The rarest standard of quiet, unclouded female beauty, the inspiration of Raphael, she buried herself in a monastery, mourning the death of the only man she loved...

Rafael Santi is a man with incredible fate, the most secret and beautiful painter of the Renaissance. The rulers of Italy envied the talent and intelligence of the brilliant painter, the fairer sex adored him for his cheerful disposition and angelic attractiveness, and for his kindness and generosity his friends nicknamed the artist the messenger of heaven. However, Contemporaries did not suspect that the magnanimous Raphael until the end of his days feared that his mind would fall into the abyss of madness.

History always has its beginning and continuation. So on April 6, 1483, in the small town of the Kingdom of Italy of Urbino, in the house of the court painter of the Dukes of Urbino and poet Giovanni Santi, the great Rafael Santi.

Giovanni Santi headed the most famous art workshop in Urbino. The tragedy in which he lost his beloved wife and mother occurred at night in his home. While the artist was in Rome, where he was painting a portrait of Pope John II, his brother Niccolò, in a fit of insanity, killed his elderly mother and seriously wounded the pregnant Maggia, the artist’s wife. The guards who arrived at the crime scene arrested the criminal, but he managed to escape. Seized with insane fear, Niccolo threw himself off the bridge into the icy river. The soldiers stood on the shore and tried to fish out the body when Majia Santi had already given birth to a baby and died from her wounds. Giovanni learned about the trouble from traveling traders. Having abandoned everything, he hurried home. But friends and neighbors have already christened the boy Raphael, buried his wife and mother.

The childhood of the great artist was very happy and carefree. Giovanni Santi, having survived a terrible tragedy, invested all his strength in Raphael, protecting him from worries and troubles real world, prevented possible errors and corrected those already committed. Since childhood, Raphael studied only with the best teachers; his father had high hopes for him, instilling a taste for painting. The first toys Raphael there were paints and brushes from my father's workshop. And already at seven years old, Rafael Santi he expressed his gifted magical fantasies in the workshop of a court painter - in the workshop of his father. Soon Giovanni remarried Bernardina Parte, the daughter of a goldsmith. From his second marriage a daughter, Elisabette, was born.

Every day the boy brought more and more joy. Giovanni watched how his son thought and acted in his fictional world, and how these weak and still clumsy hands expressed everything on canvas. He understood that talent and supernatural abilities Raphael much more worthy than his own, so he sent the boy to study with his friend, the artist Timoteo Viti.

During the training period, a ten-year-old Raphael for the first time he departed from the canons of the classical Italian portrait of the Renaissance and mastered that unique play of colors and paints, which today is a mystery for artists and art critics around the world.

In 1494, his father dies of a heart attack. little genius, and by decision of the city magistrate the boy remained in the care of the family of cloth merchant Fri Bartholomew. He was younger brother the artist Giovanni and, unlike the crazy Niccolo, was sociable, had a caring, cheerful and kind disposition, did not remain indifferent and was always ready to help those who needed it. This good-natured merchant adored his orphan nephew and spared no expense on his painting education.

Already at the age of seventeen, he easily created brilliant, talented works that still delight his contemporaries. In November 1500, a seventeen-year-old youth left his small provincial town of Urbino and moved to the bustling port city of Perugio. There he entered the workshop of the famous painter Pietro Vannucci, known under the name Perugino. Having looked at the first examination papers of his new student, the gray-haired maestro exclaimed: “Today is a joyful day for me, because I have discovered a genius for the world!”

During the Renaissance, Perugino's workshop was a creative laboratory in which brilliant individuals were trained. Perugino's deep lyricism, his tenderness, calmness and gentleness found an echo in the soul Raphael. Raphael is overbearing. He quickly masters the painting style of his teacher, studies under his guidance the work on frescoes, and becomes familiar with the technique and figurative system of monumental painting.

|

Poplar wood, oil. 17.1 × 17.3 |

Canvas (translated from wood), tempera. 17.5×18 |

Around 1504. Oil on poplar panel. 17×17 |

For some time, Raphael was still under the powerful influence of Perugino. Only timidly, like a momentary splash, an unexpected compositional solution suddenly appears, unusual for Perugino. Suddenly the colors on the canvases begin to sound unique. And, despite the fact that his masterpieces of this period are imitative, one cannot stand aside and not realize what their immortal master did. First of all, it is "", "", "". All this is completed by the created monumental canvas “” in the city of Civita - Castellan.

This is like his last bow to the teacher. Raphael goes into big life.

In 1504, he arrived in Florence, where the center of Italian art was concentrated, where the High Renaissance was born and rose.

The first thing the young man saw Raphael, setting foot on the soil of Florence, there was a majestic statue of the biblical hero David in Piazza della Signoria. This sculpture by Michelangelo could not help but stun Raphael, could not help but leave an imprint on his impressionable imagination.

At this time, the great Leonardo also worked in Florence. Just then, all of Florence watched with bated breath the duel of the titans - Leonardo and Michelangelo. They worked on battle compositions for the Council Hall of the Palace of the Signoria. Leonardo's painting was supposed to depict the battle of the Florentines with the Milanese at Anghiari in 1440. And Michelangelo wrote the battle of the Florentines with the Pisans in 1364.

Already in 1505, Florentines had the opportunity to evaluate both cardboards exhibited together.

Poetic, majestic Leonardo and rebellious, with a dazzling passion for painting Michelangelo! A real titanic battle of the elements. Young Rafael you need to come out of the fire of this battle unscorched, remaining yourself.

In Florence, Raphael masters the entire amount of knowledge that an artist needs to rise to the level of these titans.

He studies anatomy, perspective, mathematics, geometry. His search for the beautiful in Man, his worship of Man emerges more and more clearly, he develops the style of a monumentalist, his skill becomes virtuosic.

In four years, he transformed from a timid provincial painter into a real master, confidently mastering all the school secrets he needed for his work.

In 1508, a twenty-five-year-old Santi arrives at the invitation of Pope Julius II to Rome. He is entrusted with painting in the Vatican. First of all, it was necessary to make frescoes in the Signature Hall, which was allocated by Julius II for a library and office. The paintings were supposed to reflect various aspects of human spiritual activity - in science, philosophy, theology, and art.

|

|

|

|

Here he is before us not only a painter, but an artist - a philosopher who dared to rise to enormous generalizations.

The Hall of the Signature - Stanza della Segnatura - reunited the ideas of the era about the power of the human mind, the power of poetry, the rule of law, and humanity. The artist brought together philosophical ideas in live scenes.

In historical and allegorical groups Santi revives the images of Plato, Aristotle, Diogenes, Socrates, Euclid, Ptolemy. Monumental works required the master to know the most complex painting techniques - fresco, mathematical calculations and a steel hand. It was truly a titanic work!

In their stanzas (rooms) Rafael managed to find an unprecedented synthesis of painting and architecture. The fact is that the interiors of the Vatican were very complex in design. The artist was faced with almost impossible compositional problems. But Santi emerged victorious from this test.

The stanzas are masterpieces not only in terms of the plastic design of the figures, the characteristics of the images, and the color. In these frescoes, the viewer is amazed by the grandeur of the architectural ensembles created by the painter’s brush, created by his dream of beauty.

In one of the frescoes of the Signature Hall, among the philosophers and educators, as if a participant in this high debate, there is himself Rafael Santi. A thoughtful young man looks at us. Large, beautiful eyes, deep gaze. He saw everything: both joy and sorrow - and better than others he felt the Beauty that he left for people.

Raphael was the most magnificent portrait painter of all times. Images of his contemporaries Pope Julius II, Baltasar Castiglione, portraits of cardinals They depict to us proud, wise and strong-willed people of the Renaissance. The plasticity, color, and sharpness of the characteristics of the images on these canvases are amazing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In general, during his short thirty-seven-year life, the master created many unsurpassed, unique paintings. But still, the most important thing remains the inspired Madonnas, who are distinguished by their special mysterious beauty. Beauty, Kindness, and Truth are intertwined in them.

Painting " Holy Family. Madonna with Beardless Joseph“or “,” written at the age of twenty-three, represents a kind of creative “exercise” of the artist, who solved the problem of constructing a composition that was perfectly coordinated in all its parts.

Its center is marked by the figure of the Child. Highlighted by a beam of light directed directly at her, she, the brightest spot in the picture, immediately attracts the viewer’s attention. What is truly remarkable is the persistence and determination with which Santi consistently achieves impression internal relationship between characters and their spatial environment. The baby sits on Mary's lap, but his gaze is turned towards Joseph - usual for Raphael a compositional technique with which it is possible to strengthen the connection between adjacent figures not only visually, but also emotionally. Purely pictorial techniques serve the same purpose. Thus, the smooth parabolic lines outlined in the outlines of the Virgin Mary’s sleeve find an echo both in the outline of the figure of the Child and in the movement of the folds of Joseph’s cloak.

Madonna and Child - one of the leitmotifs in art Raphael: in just four years of his stay in Florence, he painted at least one and a half dozen paintings varying this plot. The Mother of God sometimes sits with the Baby in her arms, sometimes plays with him or simply thinks about something, looking at her son. Sometimes a little John the Baptist is added to them.

|

|

|

|

Thus, “”, written by him in 1512 - 1513, received the highest recognition. The mother holds the child in her arms and carries him to us, into our world. Holy Sacrament it happened - a man was born. Now life is before him. The Gospel plot is only a pretext for solving an eternal idea through a complex allegory. Life for the human being entering it is not only joy, but also quests, falls, ups, and suffering.

A woman carries her son into a cold and scary world full of accomplishments and joy. She is a mother, she anticipates the fate of her son, everything that is in store for him. She sees his future, so in her eyes there is horror, horror of the inevitable, and grief, and fear for her baby.

And yet she does not stop at the earthly threshold, she crosses it.

The Baby's face is most striking. Peering into the eyes of the Baby, unusually bright, brilliant, almost frightening to the viewer, the impression is not only of a menacing, but of something wild and “obsessed” with a meaningful look. This is God, and like God, he is also privy to the secret of his future, he also knows what awaits him in this world into which the curtain has opened. He clings to his mother, but does not seek protection from her, but as if says goodbye to her, as soon as he enters this world and accepts the full weight of the trials.

The weightless flight of the Madonna. But another moment - and she will step on the ground. She hands people the most precious thing - her son, a new person. Accept him, people, he is ready to accept mortal torment for you. This is the main idea that the artist expressed in painting.

It is this idea that awakens good feelings in the viewer, connects Santi with top names, elevates him as an artist to unattainable heights.

In the middle of the 18th century, the Benedictines sold " Sistine Madonna"to Elector Frederick Augustus II, in 1754 it ended up in the collection of the Dresden National Gallery. " Sistine Madonna"became an object of worship for all humanity. It began to be called the Greatest and Immortal picture of the world.

Image pure beauty can be seen in the portrait "". "" was painted by the artist during his stay in Florence. The image of a young beautiful girl he created is full of charm and virginal purity. This impression is also associated with the mysterious animal lying peacefully on her lap - a unicorn, a symbol of purity, female purity and chastity.

For a long time " Lady with a unicorn"was attributed either to Perugino or to Titian. It was only in the 1930s that Raphael’s authorship was discovered and confirmed. It turned out that the artist initially depicted a lady with a dog, then a mythical creature - a unicorn - appeared on her lap.

The beautiful stranger depicted Raphael, seems to be a “deity”, a “shrine”. She is in boundless harmony with the world that surrounds her.

This job Raphael like a kind of dialogue between the genius of the Renaissance and Leonardo da Vinci, who has just created his famous “ Mona Lisa”, which managed to make a deep impression on the young artist.

Using the lessons of Leonardo, the Master of Madonnas follows the teacher. He places his model in space on the balcony and against the backdrop of the landscape, dividing the plane into different zones. The portrait of the depicted model conducts a dialogue with the viewer, creating new imagery and revealing its different, not ordinary inner world.

The color scheme in a portrait also plays a huge role. A colorful and bright palette, built on a gradation of light and pure colors, gives the landscape a clear transparency, imperceptibly shrouded in a light, foggy haze. All this further emphasizes the integrity and purity of the landscape against the background of the image of the lady.

Fresco with tempera paints on wood " Transfiguration", which Raphael began writing in 1518 by order of Cardinal Giulio de' Medici for the Cathedral of Narbonne, can be perceived as the artist's artistic commandment.

The canvas is divided into two parts. At the top is the plot of the Transfiguration. The Savior with raised hands, in fluttering righteous clothes, hovers against the background of a haze illuminated by the brilliance of His own radiance. On both sides of Him, also floating in the air, are Moses and Elijah - the elders; the first, as already noted, with tablets in hands. At the top of the mountain, the blinded Apostles lie in different poses: they cover their faces with their hands, unable to bear the light emanating from Christ. On the left on the mountain there are two outside witnesses to the miracle of the Transfiguration, one of them has a rosary. Their presence does not find justification in the gospel story and was apparently dictated by some considerations of the artist unknown to us now.

There is no feeling of miracle and grace of Favorian light in the picture. But there is a feeling of emotional oversaturation of people, which overlaps the miraculous phenomenon itself.